Understanding how a grass plant grows and reproduces can be a very complex (scientific) learning process. The below link will offer interesting, yet tedious reading (For us simple ranchmen) that some grass managers might find productive in their understanding of ‘why’ some grazing-management programs are more effective than others.

One of the highlights from the article is: “Perennial grasses can produce by both buds and seed, although more than 99 percent of new tiller growth comes from the bud bank. Seed life spans are short-lived and do not extend beyond 1 year. However, buds are long-lived and have a potential life that may exceed 5 years. Since bud life varies among grass species, current research efforts are focused on determining which species have the longer living buds. Vegetative buds respond quickly to environmental changes like rain, fire, and grazing.” It should be added that disturbance of the grass plant, including grazing, trampling, mechanical, fire and even the destruction of moribund grass plants caused by desert termites’ can all effect the simulation of new growth nodes. (Nature has developed numerous recovery process over millennia)

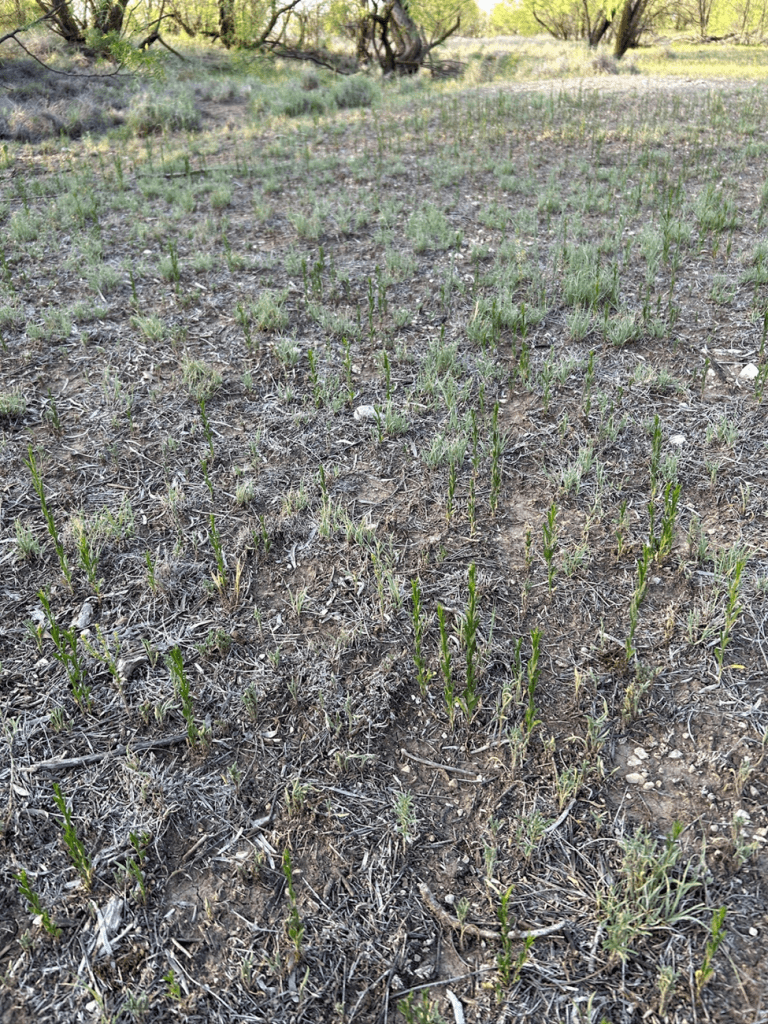

While I disagree with the statement that the seed life span is only one-year. It has been my experience that given the opportunity, seed can survive for an extremely long time and when given the opportunity (an effective graze-rest program) dormmate seed can provide excellent rangeland recovery. Albeit over an extended period. (Numerous years of application of that effective management program.)

A second highlight emphasized by the article is: “Current research has shown that perennial grasses reproduce by vegetative processes through asexual reproduction. Seed contribution to maintain an established grassland is less than 1 percent of the total reproductive effort.”

What can be gleaned form this article is that grazing-management programs should be designed to enhance bud simulation of the grass plant, seeding will take care of itself over time. (Patience is key here)

It is all about stimulating growth buds to promote rangeland recovery and after stimulation giving the plant the opportunity (REST) to reach its genetic potential.

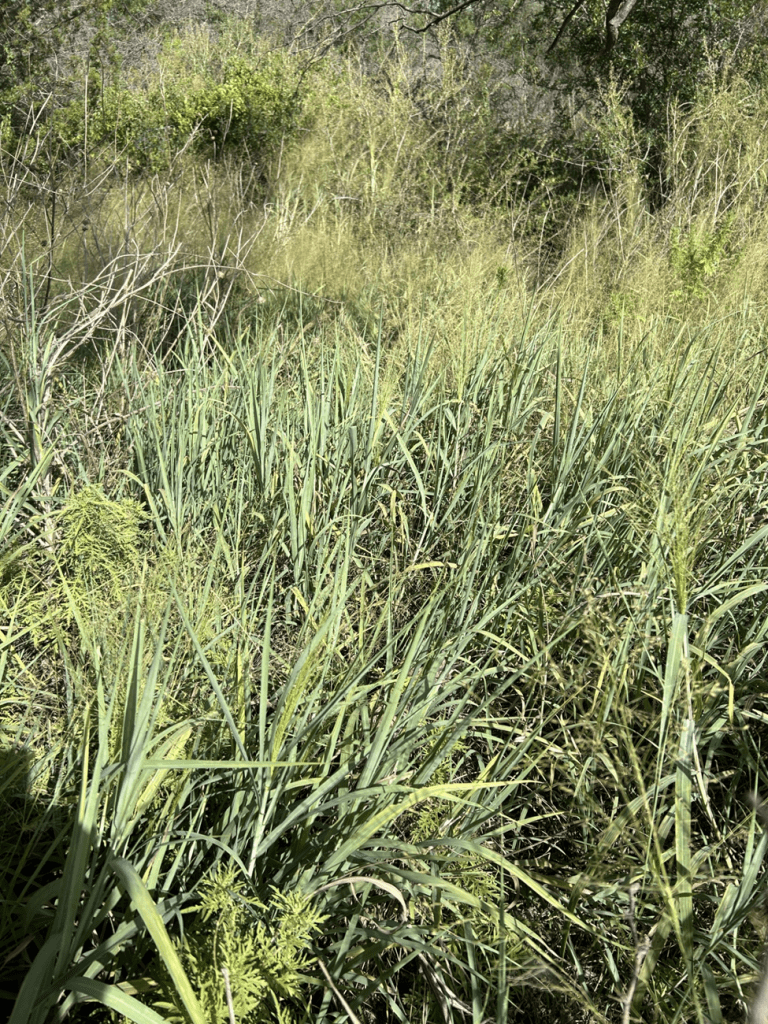

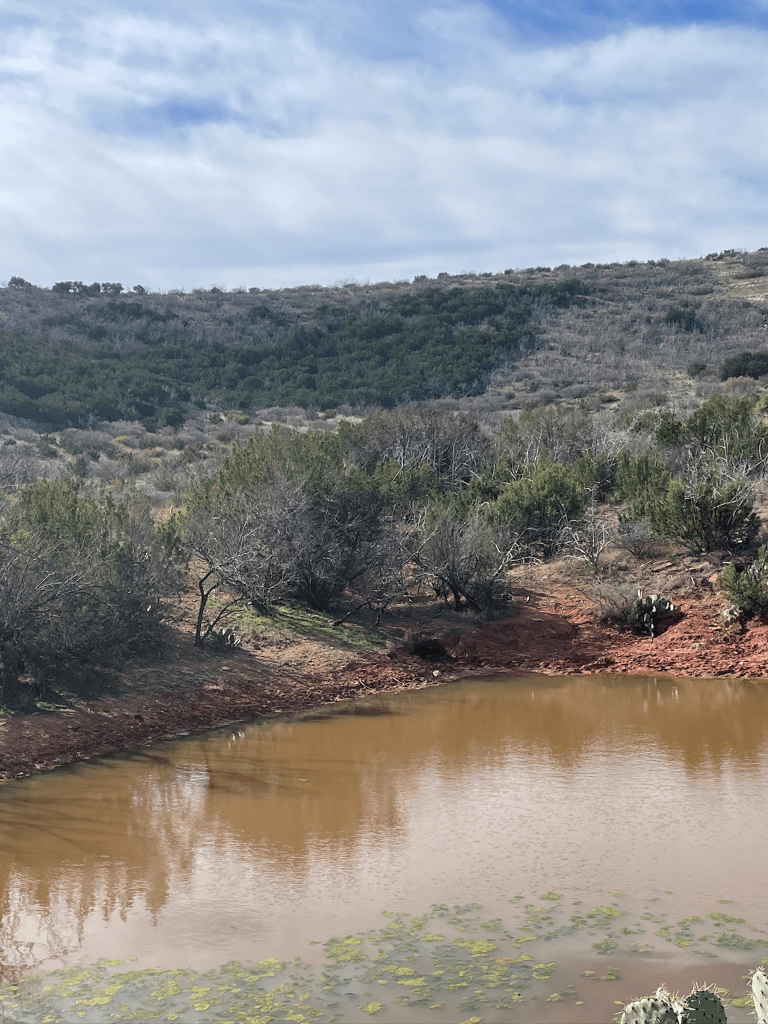

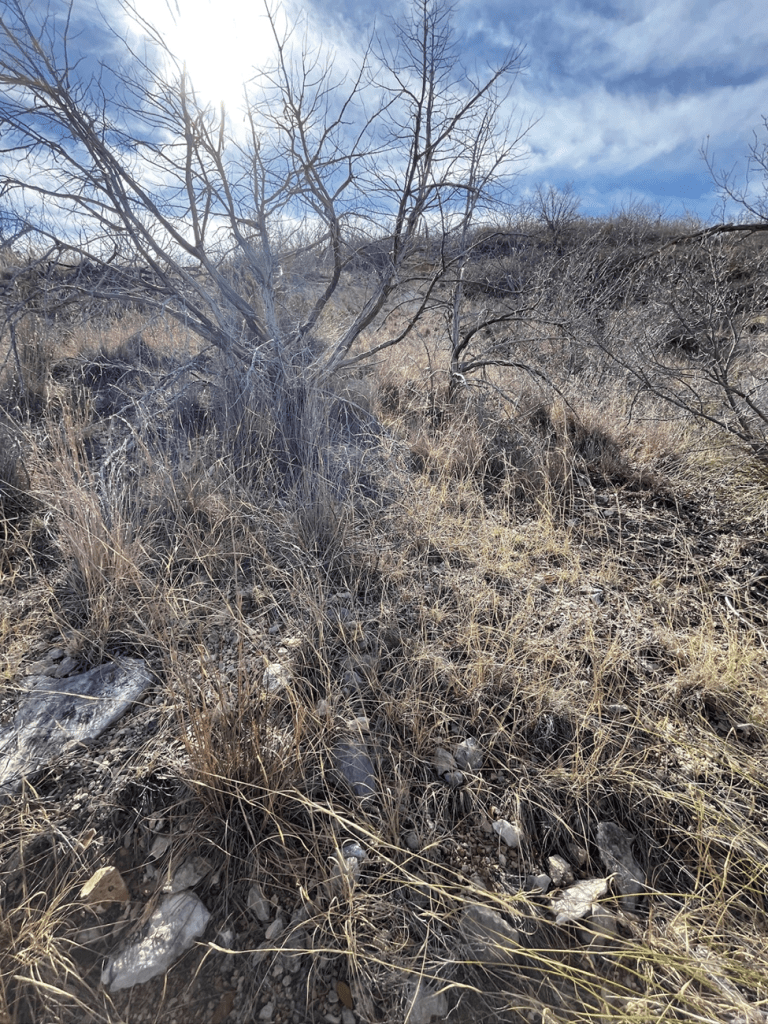

Photo shows a formerly erosive site that has almost total recovery form loss of soil. Vine Mesquite Grass is an excellent plant to quickly cover bare areas, especially when extra rain water is provided from runoff. After it is established, runoff is slowed to the point of putting the water into the ground. Greatly enhancing soil health.

THE BETTER IT GETS, THE FASTER IT GETS BETTER