The recent extended dry spell from September 1, 2021, through April 31, 2023 (14.16” for a 20-month period or an adjusted annual rainfall of 8.5” for 2 years) was devastating for most, over a wide area of Texas. Some had much less rainfall than us and the resulting lack of rangeland forage growth put most ranching operations’ future sustainability in jeopardy. Those that had an established-effective graze-rest program in place fared much better than others during this period. As some of those grazing programs had little need for expensive feeding and relocation of livestock costs. Yes, they reduced herd size dramatically, weaned calves early and utilized various other drought management protocols, as with grazing programs, drought management is essential. May to June was an established ‘sell out’ date by many in the area as little to no grazable forage remained.

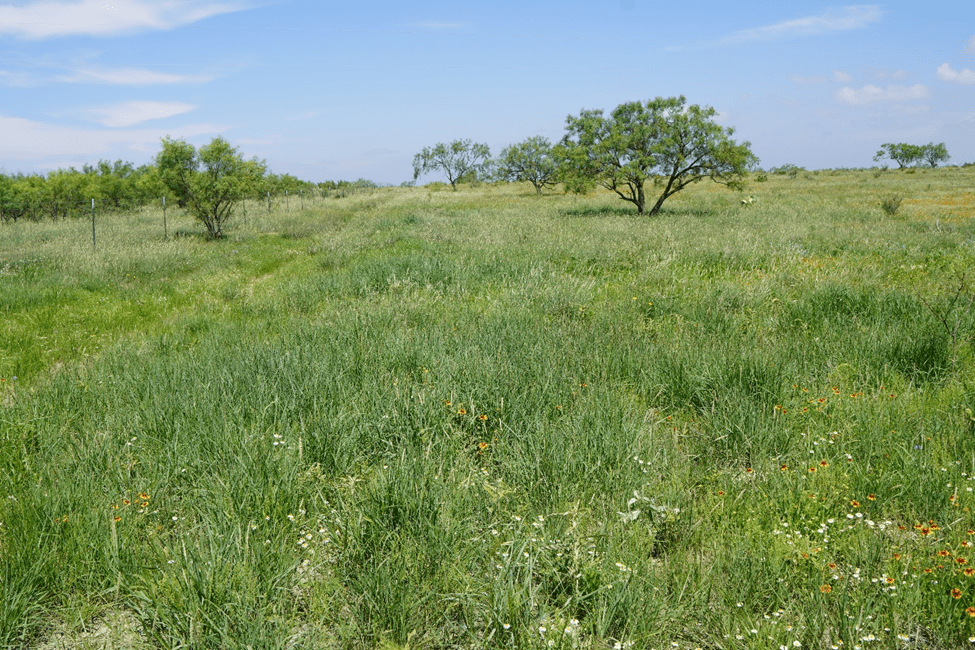

Fortunately, on May 2nd rain did begin to fall. Over the month of May and into the first week of June 4.24” fell here at the headquarters. Perfect timing for grass growth and the recovery has been phenomenal. However, as the hot days of June progress, those areas that did not have deep rooted healthy plants established prior to the dry spell are already beginning to suffer, brown-out will soon occur and growth already has ceased in many cases. Some producers are expressing concern about the density of the weed population, robbing the moisture from the grass resulting in poor grass growth, while the areas with well established-dense cover of healthy grasses are not showing those weed issues.

It is interesting that those areas that have been in an effective grazing management program the longest are showing the impressive grass growth rates the best, as some of the latest established grazing programs are obviously behind the recovery of the long time established proper grazing programs. RANGELAND RECOVERY IS A SLOW PROCESS THAT TAKES CONSIDERABLE PATIENCE OF THE PRODUCER-GRAZER. (And for that matter the research-extension-collegiate study groups. A short-term study is of little value when grazing studies are the priority.) It is notable that within some of those well-established programs of 10 plus years, the recovery is arguably to the point of conditions prior to the beginning of the dry spell and are perhaps in better condition than it was prior to the start of the dry spell. (Fresh grazable plants increasing in density and cover area.) This is impressive to say the least, as most expect recovery after drought to take several growing seasons or years to recover and get back to the pre drought point.

Perhaps the most gratifying point is that the livestock have recovered well and are gaining weight rapidly. Making the ranch operations future look much more positive than a short time ago.

The three photos below taken in the last week are a dramatic case in point. Native-not seeded Indian Grass, Big Bluestem, Little Bluestem, Texas Cup Grass, Vine Mesquite and even the lowly (In some opinions) introduced KR Bluestem are showing amazing recovery in a short 6-week period.

THE BETTER IT GETS, THE FASTER IT GETS BETTER!!